Movement clumsiness has gained increasing recognition as an important condition of childhood; however, its diagnosis is uncertain. Approaches to assessment and treatment vary depending on theoretical assumptions about etiology and its developmental course.

Over the past century, many terms have been used to describe children with clumsy motor behavior. The wide variation in labeling has depended to a large extent on cultural or professional backgrounds. For example, medical professionals use medical terms (eg, clumsy child syndrome or minimal brain dysfunction), whereas educational professionals use educational terms (eg, poorly coordinated children, movement-skill problems, or physical awkwardness).

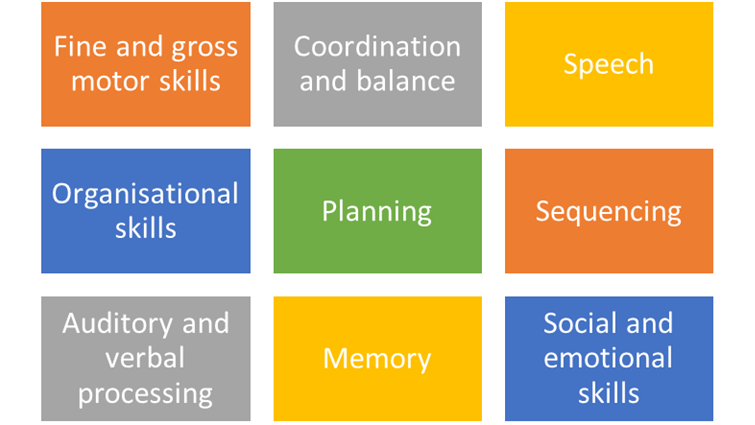

In addition, the various labels used have embodied assumptions about the etiology. Examples include developmental dyspraxia (which suggests underlying difficulties in motor planning), perceptual motor difficulties (which suggests problems in perceptual motor integration), minor neurologic dysfunction (MND), and sensory integrative dysfunction.

In response to the confusing and counterproductive heterogeneity of the labels, participants at an international multidisciplinary consensus meeting in 1994 agreed to use the term developmental coordination disorder (DCD), as described in theDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV).[1]In 2013, the diagnostic criteria were further refined with the publication of theDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5).[2]

The currently available data are insufficient to permit clear definition of the parameters of motor coordination difficulties in children. Various grades of severity and comorbidity seem to exist. Some children have only a relatively minor form of motor dyscoordination, whereas others have associated learning disabilities, attention deficit, and other difficulties.

In 1996, Fox and Lent reported that in contrast to the common belief that children grow out of motor coordination difficulties, such difficulties in fact tend to linger if no intervention takes place.[3] Intervention can be beneficial if initiated during the first years of life, while the brain is changing dramatically and new connections and abilities are being acquired.

Children with multiple conditions are at greatest risk for developing behavioral difficulties over time. Some evidence supports dividing DCD into subtypes on the basis of main features, such as ability to manipulate objects, speed of movement, ability to catch objects (eg, balls thrown, struck, or kicked during sports activities), or writing ability.

A discussion about including DCD, as currently defined, into the cerebral palsy category was held.[4] This inclusion would put DCD on the low end of the continuum of neuromotor disabilities, also described as minimal cerebral palsy, and result in a 20-fold increased incidence.[5]

Diagnostic criteria (DSM-5)

DSM-5 classifies DCD as a discrete motor disorder under the broader heading of neurodevelopmental disorders.[2] The specific DSM-5 criteria for DCD are as follows:

- Acquisition and execution of coordinated motor skills are below what would be expected at a given chronologic age and opportunity for skill learning and use; difficulties are manifested as clumsiness (eg, dropping or bumping into objects) and as slowness and inaccuracy of performance of motor skills (eg, catching an object, using scissors, handwriting, riding a bike, or participating in sports)

- The motor skills deficit significantly or persistently interferes with activities of daily living appropriate to the chronologic age (eg, self-care and self-maintenance) and impacts academic/school productivity, prevocational and vocational activities, leisure, and play

- The onset of symptoms is in the early developmental period

- The motor skills deficits cannot be better explained by intellectual disability or visual impairment and are not attributable to a neurologic condition affecting movement (eg, cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, or a degenerative disorder)